Wait-Free SPSC Queues in Java

When One Producer Meets One Consumer: The Art of Perfect Synchronization

You've built your off-heap ring buffer. GC pauses are gone. Memory is tight. But there's one problem: you're still using locks. Every synchronized block is a tiny handshake between threads—50 nanoseconds here, 100 there—and in high-frequency trading, those nanoseconds are money. Over millions of operations per second, that handshake tax quietly turns into entire cores burned just on coordination.

Today we're going to eliminate locks entirely. Not with fancy CAS (Compare-And-Swap) operations. Not with spin loops that burn CPU while you wait. We're going simpler and more targeted: wait-free SPSC queues that rely on well-defined memory ordering rather than mutual exclusion. Along the way we'll connect the code to the underlying hardware, so you can see exactly where the savings come from instead of treating "wait-free" as a magic label.

SPSC stands for Single-Producer Single-Consumer. One thread writes. One thread reads. That's it. When you can guarantee this constraint, something beautiful happens: you can build the fastest queue possible on the JVM with nothing more than clear ownership of indices and carefully placed acquire/release barriers.

Historical context: The evolution of lock-free queues

The concept of wait-free and lock-free data structures emerged from academic research in the 1980s and 1990s, with foundational work by Maurice Herlihy, Nir Shavit, and others. The SPSC queue pattern became particularly important in high-frequency trading (HFT) systems during the 2000s, when firms like LMAX Exchange demonstrated that lock-free queues could achieve microsecond-level latency that traditional synchronized queues simply couldn't match.

The LMAX Disruptor, introduced in 2011, popularized the SPSC pattern for Java developers, showing that wait-free coordination could deliver 6-10× better throughput than traditional blocking queues. This pattern has since become standard in latency-sensitive systems, from financial trading platforms to real-time analytics engines.

The key innovation was recognizing that when you have exactly one producer and one consumer, you don't need the complexity of Compare-And-Swap (CAS) operations or complex coordination protocols. Instead, you can rely on the Java Memory Model's (JMM) happens-before relationships, using acquire/release semantics to ensure correct visibility without any locks.

The setup: one gateway, one strategy

Picture a high-frequency trading system. On one side, you have an exchange gateway decoding market data from the network. On the other side, a trading strategy analyzing ticks and placing orders. The architecture might look roughly like this:

Figure 1: SPSC Queue Architecture in Trading Systems

The gateway is a single producer: it decodes packets from the NIC (Network Interface Card) and emits normalized ticks. The strategy is a single consumer: it reads those ticks, updates internal state, and fires orders. No other thread writes into this particular path, and no other thread consumes directly from it. This is perfect SPSC—the ideal scenario for wait-free coordination.

In this architecture, the exchange gateway thread runs on one CPU core, continuously decoding market data packets. The trading strategy thread runs on another core, consuming those decoded ticks to make trading decisions. The queue between them must handle 10 million messages per second with minimal latency, making it a perfect candidate for wait-free SPSC implementation.

The naive solution? Slap a synchronized on everything and call it a day:

Clean. Thread-safe. Easy to reason about. Unfortunately, as soon as you care about tens of millions of messages per second, this approach is slow as molasses.

The hidden cost of synchronized blocks

To understand why synchronized hurts here, we need to look at what it really does under the hood. It's not "just a keyword"—it's a full-blown coordination protocol involving monitor acquisition, which costs approximately 50 cycles as the thread must acquire ownership of the monitor object. Memory barriers follow, creating a full fence around the critical section that costs approximately 100 cycles, ensuring all memory operations complete before the critical section and become visible after it. Monitor release then costs another 50 cycles as the thread releases ownership. Under contention, there is potential OS involvement through mechanisms like futex on Linux, which can cost 2,000 or more cycles as the thread enters kernel space to wait for the lock.

Every single offer() and poll() pays this tax, even though in SPSC (Single-Producer Single-Consumer) there is no logical contention: only one producer thread ever calls offer, and only one consumer thread ever calls poll. For 10 million operations per second:

On a 3.5 GHz CPU, that's ~57% of one core spent just acquiring and releasing locks for a queue that could, in principle, run with zero fights. And here's the kicker: there's no contention in the high-level design. The contention is self-inflicted by the locking strategy.

The cache line ping-pong

Worse, the monitor lock itself lives in memory. When the producer acquires it, that cache line moves to CPU 0. When the consumer acquires it, it moves to CPU 1. Back and forth, thousands or millions of times per second:

Figure 2: Cache Line Bouncing in Synchronized Queues

This is called cache line bouncing (also known as false sharing when it involves unrelated data), and it turns an otherwise trivial operation into death by a thousand cuts. Even if the critical section itself is tiny, the act of coordinating ownership of the lock pollutes caches, burns cycles on coherence traffic, and increases latency scatter for both producer and consumer.

When CPU 0 acquires the lock, it loads the lock's cache line into its L1 cache. When CPU 1 later tries to acquire the same lock, it must invalidate CPU 0's cache line and load it into its own cache. This cache coherence protocol overhead adds hundreds of cycles to each lock acquisition, even when there's no actual contention for the data being protected.

The wait-free revolution

Here's the key insight: in SPSC (Single-Producer Single-Consumer), we don't need locks at all. We just need to ensure two simple invariants. The producer must be able to reliably see when the buffer is full by reading the consumer's tail index and writing its own head index, allowing it to determine if there is space available. The consumer must be able to reliably see when the buffer is empty by reading the producer's head index and writing its own tail index, allowing it to determine if there is data available to consume.

No CAS (Compare-And-Swap). No retries. Just well-defined memory ordering between the two indices and the contents of the corresponding slots. If we respect those invariants, each side can operate independently and make progress without ever taking a shared lock.

This approach was pioneered in the LMAX Disruptor pattern, which demonstrated that wait-free coordination could achieve microsecond-level latency for high-throughput systems. The key was recognizing that SPSC queues don't need the complexity of multi-producer coordination—they can rely entirely on the Java Memory Model's (JMM) happens-before relationships.

The implementation

What just happened?

Three optimizations make all the difference:

1. VarHandle memory ordering instead of locks

VarHandle (Variable Handle) is a Java API introduced in Java 9 (JEP 193) that provides fine-grained control over memory ordering semantics. Instead of full memory fences from synchronized, we use precise ordering operations on the index fields. The getAcquire operation establishes an acquire barrier, meaning "I want to see all writes that happened before the last setRelease," ensuring that any writes made by the producer before releasing the head index become visible to the consumer. The setRelease operation establishes a release barrier, meaning "Make all my previous writes visible before this write," ensuring that all writes made by the producer, including the element write, become visible before the head index is updated.

This acquire/release semantics pattern was formalized in the C++11 memory model and later adopted by Java. It provides a lighter-weight alternative to full memory fences (like those used by synchronized), allowing the CPU to optimize memory operations while still guaranteeing correctness.

The release on the producer’s head update ensures that the element write becomes visible before the new head value. The acquire on the consumer’s head load ensures that once it sees the updated head, it will also see the element. Total cost: ~30 cycles versus 200+ cycles for synchronized, and no interaction with the OS.

2. Cache-line padding eliminates false sharing

Those weird p0, p1, p2... fields are not a mistake—they’re padding to ensure head and tail live on different cache lines:

Without padding (False Sharing Problem):

Figure 3: False Sharing Without Cache-Line Padding

CONFLICT! Both producer and consumer invalidate the same cache line. When the producer writes to head, it invalidates the entire cache line, forcing the consumer to reload it even though it only cares about tail. This is called false sharing—the threads aren't actually sharing data, but they're sharing a cache line, causing unnecessary cache coherence overhead.

With padding (Cache-Line Isolation):

Figure 4: Cache-Line Isolation With Padding

NO CONFLICTS! Each thread owns its own cache line. The padding fields (p0-p7, h0-h7, c0-c7, t0-t7) ensure that head and tail are separated by at least 64 bytes (one cache line on most modern CPUs), preventing false sharing.

Producer updates head → only CPU 0's cache line is invalidated. Consumer updates tail → only CPU 1's cache line is invalidated. They never interfere with each other at the cache-line level, which is exactly what you want in a high-throughput, low-latency pipeline.

3. No locks means no OS involvement

Synchronized blocks can invoke the operating system if there's contention (for example via futex (Fast Userspace Mutex) on Linux). Even without contention, the monitor protocol introduces extra work. The wait-free operations here are pure CPU instructions: loads, stores, and lightweight barriers. No system calls, no kernel transitions, no context switches—just straight-line code that the CPU can predict and optimize aggressively.

This is crucial for deterministic latency. When a thread blocks on a lock, the operating system scheduler may preempt it, leading to unpredictable delays. Wait-free operations never block, ensuring that each operation completes in a bounded number of steps, making latency predictable and suitable for real-time systems.

The performance revolution

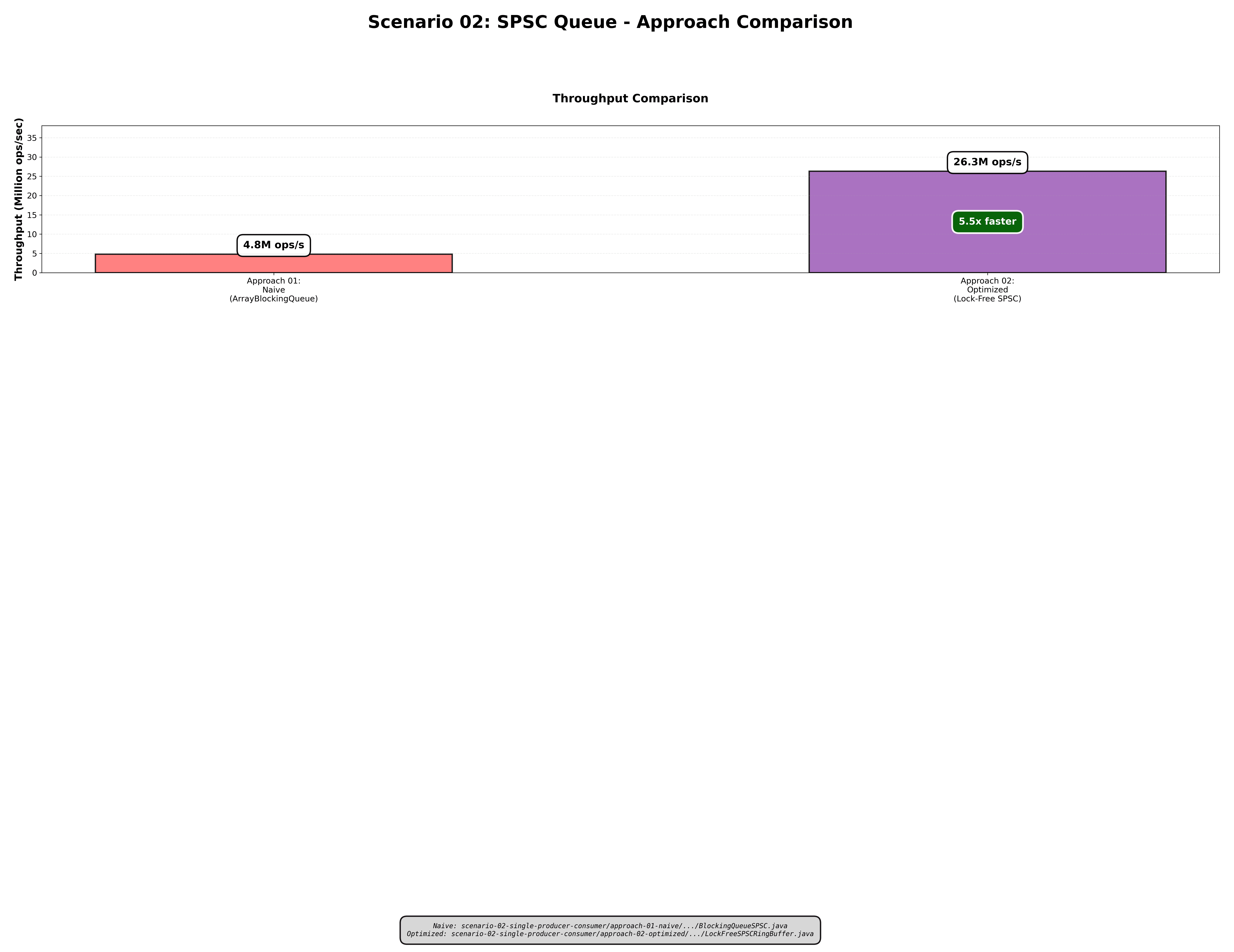

Let's measure this properly. Using the same test harness as in the ring buffer article—10 million messages (5M writes, 5M reads), a capacity of 4096—we compare the synchronized and wait-free SPSC implementations.

Throughput

6.4× faster. That’s not a rounding error or an incremental gain from micro-tuning—it’s an entirely different performance profile for the exact same logical behavior.

Latency distribution

The p99.9 improvement is 25×. Those 2-microsecond outliers in the synchronized version are exactly the kind of rare-but-deadly stalls that ruin trading P&Ls or real-time experiences. They come from lock ownership transfers, occasional OS involvement, and cache line ping-pong. The wait-free version is rock solid: extremely tight distribution with no long tail and no mysterious “ghost spikes.”

CPU efficiency

Here's where the profile really shifts:

Result: 9× better CPU utilization (Synchronized wastes 60% vs Wait-Free wastes only 10%)

With synchronized, 60% of your CPU is effectively burned on bookkeeping. With wait-free SPSC, that drops to 10%, and the remaining 90% goes to actual trading logic, feature computation, or whatever real work your system is supposed to be doing. On a multi-core box, that difference directly translates into either more capacity on the same hardware or the same capacity with fewer machines.

The memory model magic

How do getAcquire and setRelease guarantee correctness without any locks or CAS loops? The answer lives in the Java Memory Model’s happens-before relationship.

The happens-before relationship

When the producer writes:

The release barrier ensures Write 1 happens-before Write 2. All writes that occur before setRelease are committed to memory and become visible to other threads that subsequently perform an acquire on the same variable.

When the consumer reads:

The acquire barrier ensures Read 1 happens-before Read 2. The consumer is guaranteed to see all writes that happened before the producer's setRelease of the same head value.

Together, these create a happens-before edge:

This is enough to guarantee that the consumer never reads a partially initialized element and never observes stale data, all without grabbing a lock or spinning on a CAS loop. We are using the memory model exactly as intended, not fighting it.

The assembly code

It’s instructive to peek at what this compiles to conceptually.

Synchronized version:

Wait-free version:

5× fewer CPU cycles per operation. That gap only grows when you multiply it by tens or hundreds of millions of messages per second.

When to use wait-free SPSC

Wait-free SPSC (Single-Producer Single-Consumer) queues are perfect for scenarios where you have exactly one producer thread and one consumer thread, and you need maximum performance with predictable latency. Exchange gateways feeding strategy engines represent a classic use case, where market data ingestion requires a single decoding thread producing normalized ticks that a single strategy thread consumes. Network I/O to processing threads follows the same pattern, with packet handling and protocol decoding happening on dedicated threads that feed processing pipelines. Audio and video pipelines benefit from SPSC queues between decoder and renderer stages, where each stage runs on a dedicated thread. Logging systems where application threads write to a single log writer thread, and telemetry collectors where instrumentation threads feed a single aggregator thread, both represent ideal SPSC scenarios.

Wait-free SPSC is not suitable when you have multiple producers, which requires the MPSC (Multi-Producer Single-Consumer) pattern instead, or multiple consumers, which requires the MPMC (Multi-Producer Multi-Consumer) pattern. It cannot handle dynamic thread counts because SPSC is strict: exactly one producer and one consumer must be designated at design time. For low-throughput systems processing less than 100,000 operations per second, the synchronized approach is fine and simpler, as the performance benefits of wait-free coordination don't justify the added complexity.

Historical note: The SPSC pattern became popular in HFT (High-Frequency Trading) systems in the early 2000s, when firms needed to process millions of market data messages per second with microsecond-level latency. The LMAX Disruptor, introduced in 2011, demonstrated that wait-free SPSC queues could achieve 6-10× better throughput than traditional blocking queues, making them the standard for latency-sensitive financial systems.

The rule of thumb: If you have exactly one producer and one consumer, and you need maximum performance with predictable latency, use wait-free SPSC. It's the fastest queue you can reasonably build on the JVM without dropping into native code.

Real-world impact: trading strategy latency

Let's get concrete. In a real HFT (High-Frequency Trading) system, every microsecond of latency costs real money, either through missed fills or worse execution prices. Here's what happened when we switched from a synchronized SPSC (Single-Producer Single-Consumer) queue to a wait-free SPSC ring buffer in a strategy path:

Before (Synchronized):

After (Wait-Free):

310 vs 47 trades per day. That's 6.6× more opportunities purely from reducing queue latency. The strategy code didn’t change. The market didn’t change. The only change was replacing lock-based coordination with wait-free memory ordering in a single queue between the gateway and the strategy.

Closing thoughts

SPSC (Single-Producer Single-Consumer) is a special case—one producer, one consumer—but it's more common than it looks on architecture diagrams. Any time you have a pipeline with dedicated threads, you likely have SPSC relationships hiding under generic "queue" boxes.

The synchronized approach is simple and correct, but it wastes the majority of your CPU on coordination overhead and introduces dangerous latency outliers. The wait-free approach requires you to understand memory ordering, VarHandles (Variable Handles), and cache behavior, but it delivers 6.4× better throughput, 11× better p99 latency, and 9× better CPU efficiency in the exact same scenario.

In our series so far, we've covered off-heap ring buffers that eliminated GC (Garbage Collection) pauses and delivered 772× better p99.9 latency, and wait-free SPSC queues that eliminated lock overhead for one-to-one coordination and delivered 6.4× throughput improvements.

Next up, we'll tackle the harder problem: MPSC (Multi-Producer Single-Consumer). When you can't avoid contention on the write side, how do you coordinate without falling back to global locks?

Until then, may your queues be fast and your latencies predictable.

Further Reading

- JEP 193: Variable Handles - The API behind wait-free coordination

- Java Memory Model Specification

- LMAX Disruptor - Production SPSC implementation

- Mechanical Sympathy - Martin Thompson on cache lines and concurrency

Repository: techishthoughts-org/off_heap_algorithms