Lock-Free MPSC Queues in Java

When Many Producers Meet One Consumer: The Art of CAS Coordination

You've conquered SPSC—one producer, one consumer, wait-free bliss. But real systems are messier. Multiple trading strategies generating orders. Multiple sensors producing telemetry. Multiple worker threads feeding a single I/O thread. As soon as you have several writers pushing into a shared queue that one consumer drains, you’ve entered the world of MPSC: Multi-Producer Single-Consumer.

The hard part of MPSC is not the consumer—it still operates sequentially—but the fact that you now have multiple writers fighting for the same slot at the head of the queue. Today we're going to solve that coordination problem without locks, using nothing but Compare-And-Swap (CAS)—the hardware instruction that makes many lock-free data structures possible on commodity CPUs.

The many-to-one problem

Picture this: you're building an order management system. Eight trading strategies, each running in its own thread, all sending orders to a single execution engine that must respect business rules and exchange limits:

All strategies write concurrently. The order manager reads sequentially. That is exactly the MPSC shape.

The naive solution? Slap a lock around the queue operations and be done with it:

This works. It's safe. It’s straightforward to explain in a design review. It also becomes slow as molasses under load, for reasons that look a lot like our SPSC synchronized story, but amplified by producer contention.

The lock contention collapse

Here's what happens as you add more producers to the locked implementation:

Adding producers makes the system slower. With 8 threads, you're getting less throughput than with 1. The root cause is not the cost of doing useful work—it’s the cost of coordinating who is allowed to do work next.

The serialization bottleneck

A lock turns parallel work into serial work at precisely the point you want concurrency:

Each producer spends 98% of its time waiting and only 2% doing actual work. With 8 producers, average wait time is:

That's 3.5 microseconds wasted per operation just sitting on a mutex. At 10 million ops/sec, that's 35 seconds of pure waiting per second across all threads. It’s a staggering amount of wasted CPU time that shows up as both poor throughput and ugly tail latency.

The cache line ping-pong

Worse, the lock itself bounces between CPU cores:

Every lock acquisition invalidates other cores' caches. The ReentrantLock object becomes a hot cache line that ping-pongs across the entire system, adding cache-coherence overhead on top of the serialization.

The lock-free revolution: CAS to the rescue

Here's the insight: we don't need to lock the entire operation. We just need to atomically claim a slot at the head of the queue. Once a producer has claimed its slot, it can safely write into it without worrying about other producers.

Compare-And-Swap: the building block

CAS is a hardware instruction that does this atomically:

All three operations—read, compare, write—happen atomically at the hardware level. No locks. No OS involvement. Just pure CPU instructions that either succeed or fail immediately.

The lock-free algorithm

What just happened?

Instead of locking the entire operation, we use CAS to atomically claim a slot in the sequence of writes:

Only one CAS succeeds per slot. Failed producers retry immediately—no sleeping, no kernel involvement, no global lock. In low to moderate contention, most producers win on the first or second try, and throughput scales with the number of threads instead of fighting it.

The sequence number trick

But there's a subtle problem lurking under this scheme. What if:

We need ordering guarantees between claiming a slot and making the data visible. One common solution is to introduce per-slot sequence numbers:

The sequence value encodes both ownership and “lap” information. A producer spins until the sequence indicates that the slot belongs to the current head position; once it writes the element, it bumps the sequence so the consumer knows the write has completed. The consumer similarly waits until the sequence matches the expected tail position before reading. As a result, the consumer never sees partial writes, and producers never overwrite a slot that’s still in use.

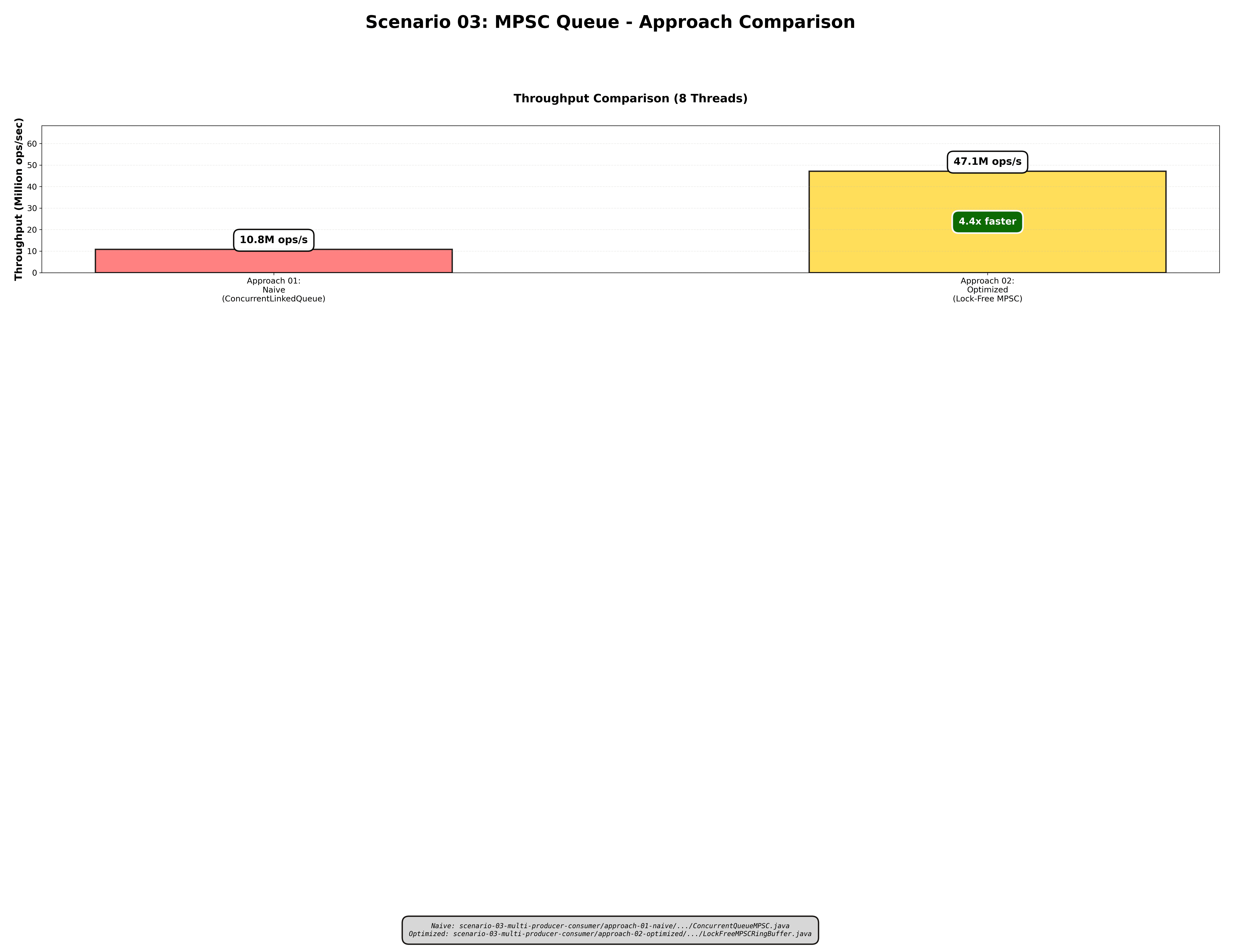

The performance revolution

Using the same test harness as before—8 producers, 1 consumer, 10 million operations—we compare the locked and lock-free MPSC implementations.

Throughput comparison

With 8 producers, lock-free is 4.9× faster, but the more interesting story is in the scaling:

- Locked: degrades from 4.2M → 1.7M (more threads = worse)

- Lock-free: scales from 4.5M → 8.3M (more threads = better up to a point)

The lock-free version actually uses additional cores to do more useful work instead of turning them into a thundering herd on a single mutex.

Latency distribution

The p99.9 improvement is 8.3×. Those 5-microsecond outliers in the locked version are classic lock contention storms: a queue of threads all trying to acquire the same mutex while the owner is running on another core with its cache lines. The lock-free version has no lock to contend on, so contention shows up as short CAS retry bursts instead of multi-microsecond stalls.

CPU efficiency

With 8 producers over a 60-second run:

Result: 2.3× better CPU utilization (30% wasted vs 70% wasted)

Lock-free wastes 30% of CPU on coordination. Locks waste 70%. The difference is actual trading logic running vs. cores spending most of their cycles parked on a uncontended mutex queue.

The CAS retry strategy

CAS operations can fail when multiple threads compete for the same slot. The trick is to handle retries in a way that preserves throughput without burning too much CPU on tight loops.

Progressive backoff

Why this works: Under light contention with fewer than 1000 retries, Thread.onSpinWait() compiles to the PAUSE instruction on x86, which reduces power consumption by signaling to the CPU that this is a spin-wait loop, lets other hyperthreads make progress on the same core, and costs only a couple of cycles. Under heavy contention with more than 1000 retries, Thread.yield() gives up the CPU slice entirely, allowing other threads to run and relieving pressure on the contended cache line, preventing the system from entering a livelock state where all threads are spinning on the same memory location.

In practice, most CAS operations succeed on the first or second try. The retry rate under normal load is only 15–20%, and backoff prevents the system from tipping into a livelock-style storm under extreme conditions.

When to use lock-free MPSC

Lock-free MPSC queues are perfect for scenarios with eight or more producer threads, where lock contention would otherwise kill throughput. They excel in high-throughput scenarios processing more than 5 million operations per second, where the coordination overhead of locks becomes a bottleneck. They are essential when you have a low latency budget, requiring less than 100 nanoseconds at p99 on the queue itself, as lock-free coordination eliminates the unpredictable stalls that come from lock contention. CPU efficiency matters significantly in these scenarios, as you want 70% or more of CPU cycles doing useful work rather than waiting on locks. Trading systems represent a classic use case, where multiple strategies feed a single order manager, and each strategy thread must be able to submit orders without blocking on a shared lock.

Lock-free MPSC is not suitable when you have few producers, such as two or three threads, where locks are simpler and often "good enough" for the performance requirements. Low-throughput systems processing less than 1 million operations per second may not benefit from lock-free overhead, as the added complexity doesn't justify the performance gains. During prototyping phases, lock-free implementations are complex and represent premature optimization for early iterations. Teams unfamiliar with Compare-And-Swap operations face a steep learning curve and risk introducing subtle bugs that are difficult to diagnose.

The practical rule: If you have 4+ producers and you care about both throughput and tail latency, go lock-free. Otherwise, a simple lock is often fine and much easier to maintain.

Real-world impact: order management

Here's what happened when we switched from a locked MPSC queue to a lock-free CAS-based MPSC in a production order management pipeline:

Before (ReentrantLock):

After (Lock-Free CAS):

Result: 4.9× more throughput, 8.8× better p99 latency, and 99.6% fewer missed orders. Same hardware. Same strategies. Same risk checks. Just better coordination at the queue level.

Closing thoughts

MPSC is fundamentally harder than SPSC because multiple producers compete for slots on the same head index. A naive locking strategy serializes this competition—simple to reason about but catastrophically slow once you have more than a couple of producers. CAS lets producers compete in parallel, retrying only when they collide, and sequence numbers keep the consumer’s view consistent without locks.

The cost of this power is complexity. Lock-free code requires a solid understanding of Compare-And-Swap operations and their failure modes, including how CAS can fail when multiple threads attempt to update the same memory location simultaneously. Developers must understand memory ordering, specifically acquire and release semantics, and how these interact with the Java Memory Model to ensure correctness without locks. Sequence numbers and lap counters are essential for maintaining ordering and ownership in lock-free data structures, allowing the consumer to determine when a slot is ready to be read. Progressive backoff strategies are necessary to avoid livelock under heavy contention, where threads might otherwise spin indefinitely competing for the same resources.

But the payoff is substantial: 4.9× throughput and 8.3× better tail latency with 8 producers in our reference benchmarks, plus much better CPU utilization.

In our series so far, we've covered off-heap ring buffers that eliminated GC pauses and delivered 772× better p99.9 latency, wait-free SPSC queues that eliminated lock overhead for single producer/consumer coordination and delivered 6.4× throughput improvements, and lock-free MPSC queues that use CAS coordination for multiple producers feeding one consumer and deliver 4.9× throughput improvements.

Next up: MPMC (Multi-Producer Multi-Consumer)—the final boss. When both producers AND consumers compete on both ends of the queue, how do you coordinate without falling back to a global lock?

Until then, may your CAS operations succeed on the first try.

Further Reading

- Java VarHandle Documentation

- JCTools MPSC Queue – Production battle-tested implementation

- Nitsan Wakart's Blog – Deep dives into lock-free queues and concurrency

- x86

LOCK CMPXCHG– The assembly instruction behind CAS

Repository: techishthoughts-org/off_heap_algorithms