In our previous article, we explored the historical evolution of Object-Oriented Programming and touched on the challenges it faces in concurrent environments. Today, we'll dive deep into the specific headaches that emerge when multiple threads interact with shared mutable state – problems that have plagued developers for decades.

The Fundamental Problem: Shared Mutable State

Imagine Arthur and Maria both trying to purchase the last available ticket for a concert through a web application. Both click "Buy Now" at exactly the same time. What happens next illustrates the core challenges of concurrent programming:

Without proper synchronization, both Arthur and Maria might see availableTickets > 0, leading to both "successfully" purchasing the same ticket.

The Four Horsemen of Concurrent Programming

When multiple threads interact with shared state, four primary problems can arise, each more insidious than the last.

State diagram showing the four primary concurrency failure modes and how they lead to system problems. The Actor Model eliminates these issues through message passing and sequential processing within actors.

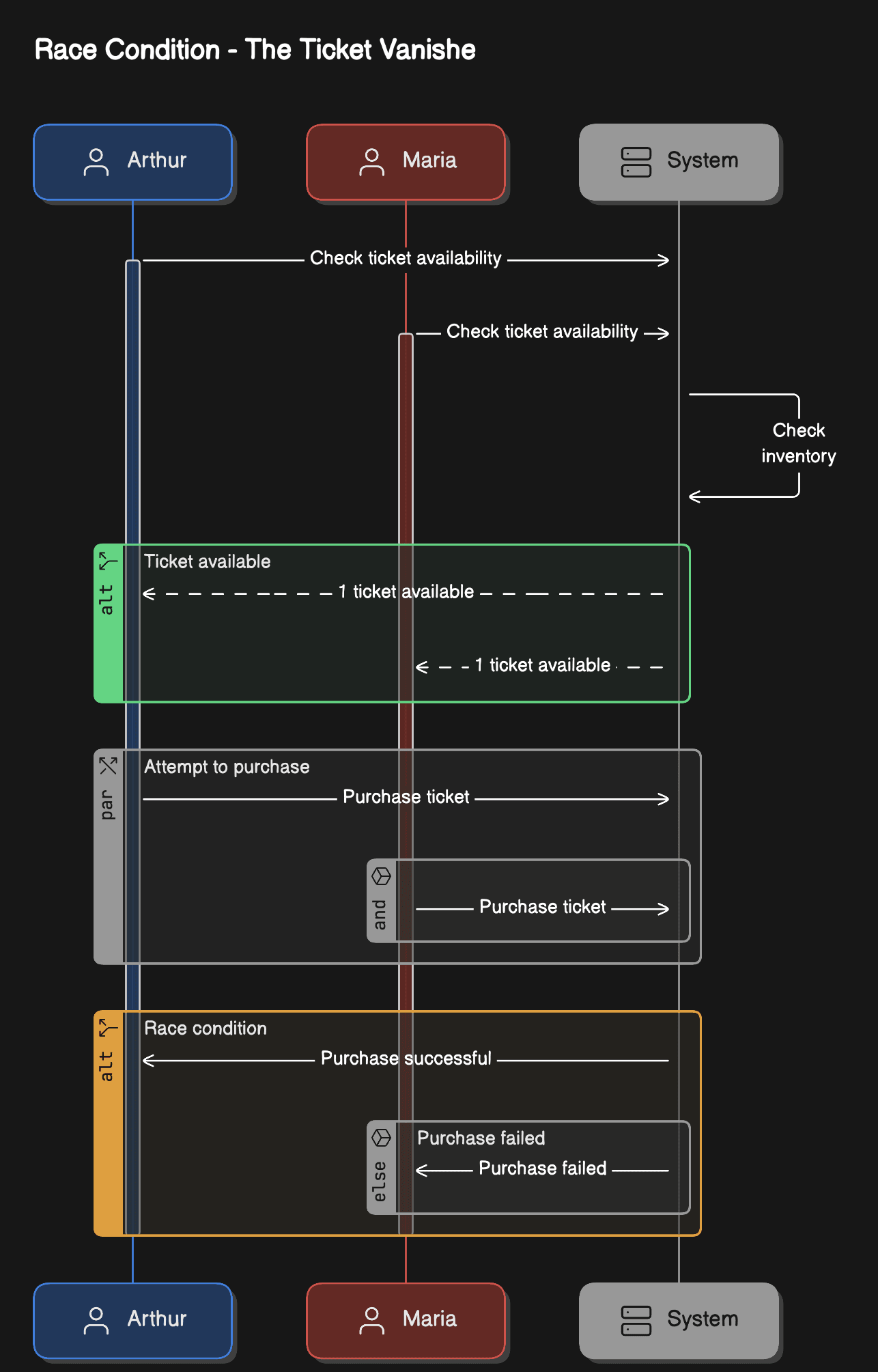

1. Race Conditions

Race conditions occur when the outcome of a program depends on the timing and interleaving of threads. The ticket example above is a classic race condition.

The result? The system thinks it sold two tickets when only one was available, leading to data corruption and unhappy customers.

This sequence diagram visualizes the exact timing issue in the race condition. Both Arthur and Maria check availability before either decrements, resulting in both "successfully" purchasing the same ticket.

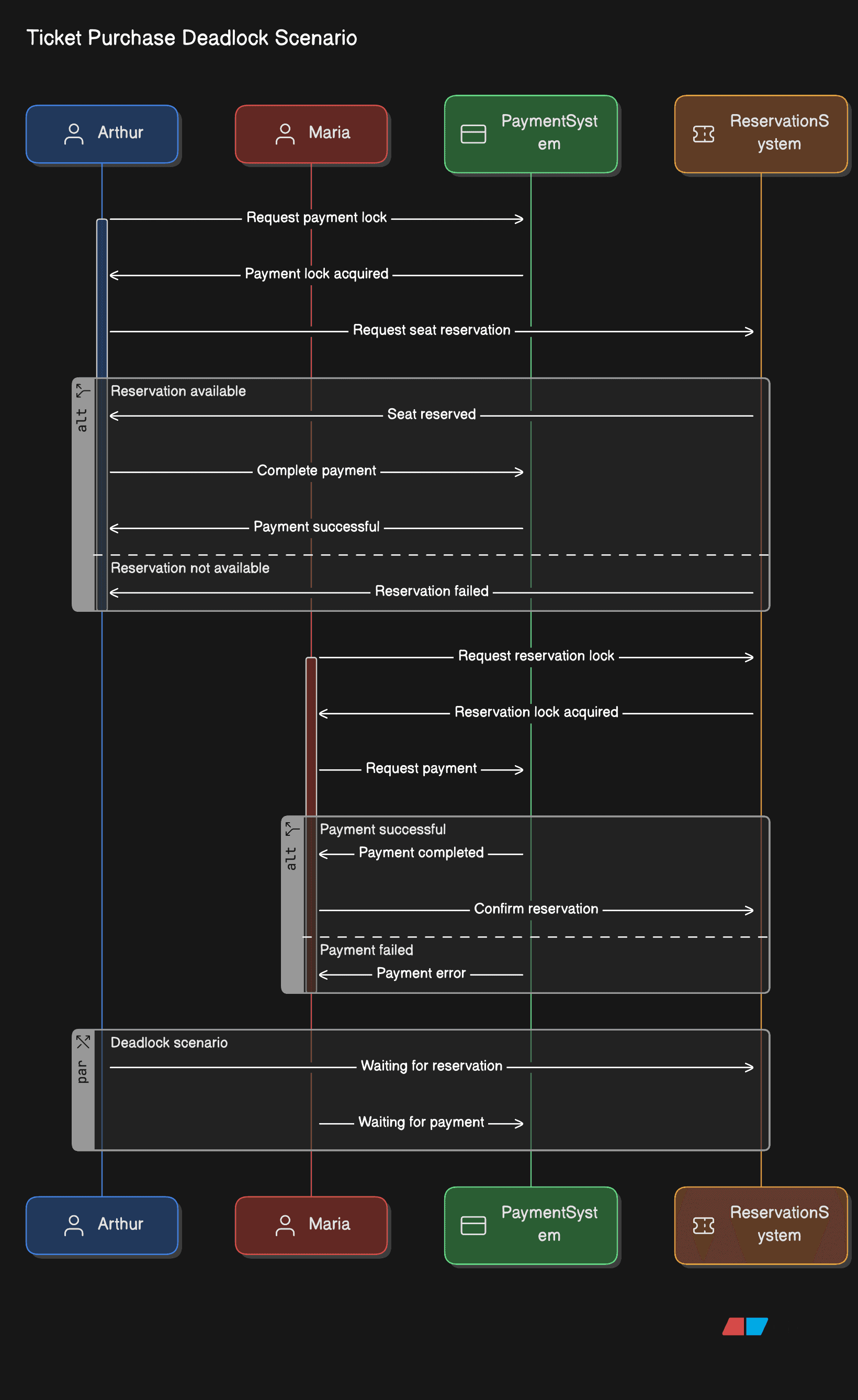

2. Deadlocks

Deadlocks happen when two or more threads are blocked forever, waiting for each other to release resources:

If Thread 1 acquires lock1 while Thread 2 acquires lock2, they'll wait forever for each other.

This sequence diagram shows the circular dependency that creates a deadlock. Thread 1 holds lock1 and waits for lock2, while Thread 2 holds lock2 and waits for lock1. Neither can proceed.

3. Livelocks

Livelocks are similar to deadlocks, but threads aren't blocked – they're actively trying to resolve the conflict, creating an infinite loop of politeness:

The threads remain active but make no progress, like two people in a hallway both stepping left and right in sync.

Livelock flow: threads continuously detect conflicts and yield to each other, but both make the same decision simultaneously, resulting in an infinite loop of mutual yielding without progress.

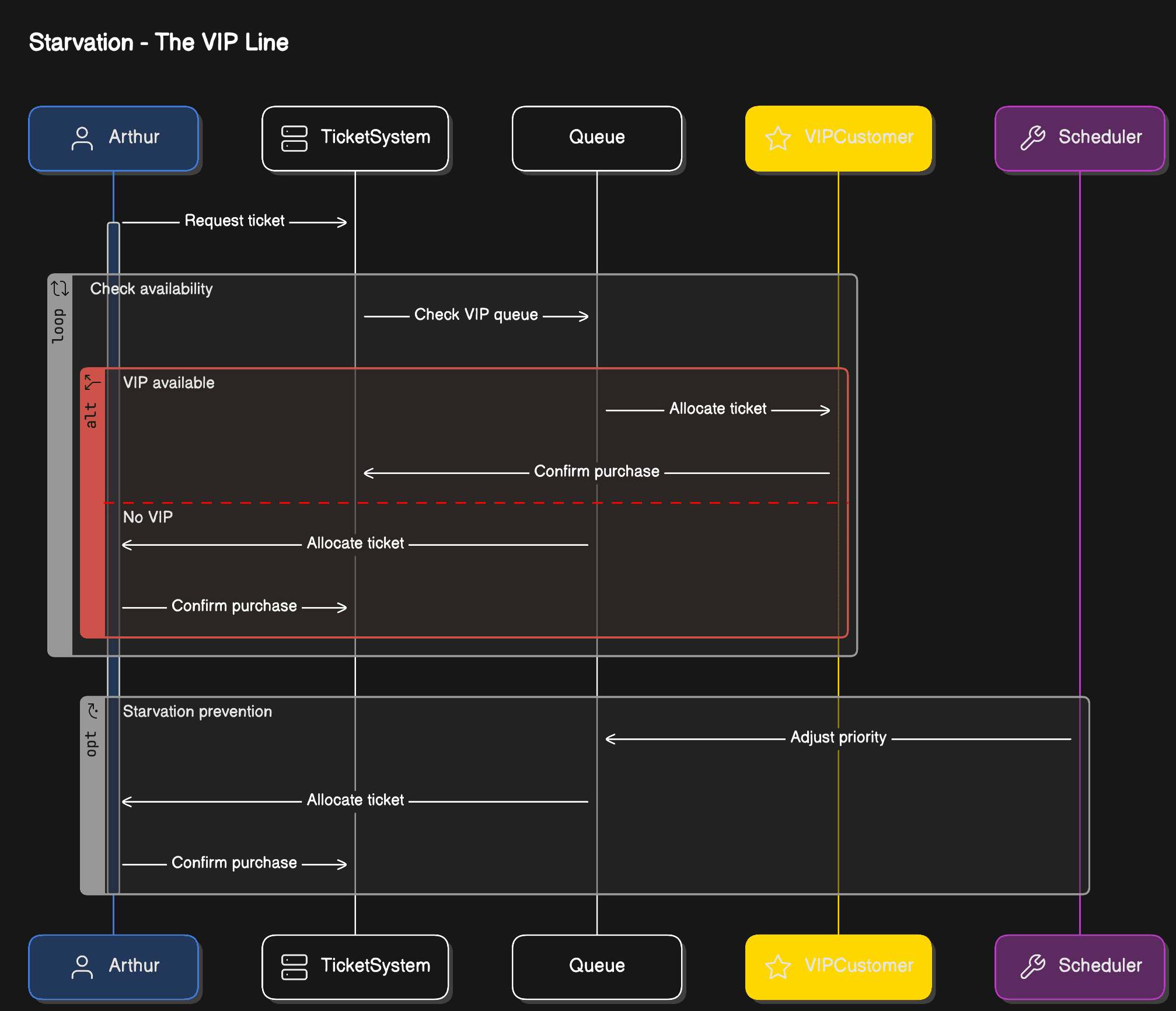

4. Starvation

Starvation occurs when a thread is perpetually denied access to resources it needs:

Low-priority threads might wait indefinitely while high-priority threads continuously grab resources.

Traditional Solutions and Their Limitations

Java provides several mechanisms to handle these issues, but each comes with trade-offs:

Synchronized Keywords

Pros: Simple, prevents race conditions Cons: Poor scalability, potential for deadlocks

Volatile Fields

Pros: Ensures visibility of changes across threads Cons: Only works for single operations, doesn't prevent race conditions in complex operations

Atomic Classes

Pros: Better performance than synchronized Cons: Limited to simple operations, doesn't solve complex coordination

The Caching Conundrum

Modern applications often add caching layers for performance, which introduces additional complexity:

Now we have to worry about:

- Cache invalidation across multiple instances

- Consistency between cache and database

- Distributed locking in clustered environments

Why OOP Struggles with Concurrency

Object-Oriented Programming's core principle of encapsulation assumes that objects can protect their internal state. But when multiple threads access the same object, this protection breaks down:

- Encapsulation isn't enough: Private fields don't protect against concurrent access

- Method-level synchronization is too coarse: It creates unnecessary bottlenecks

- Complex object graphs require complex locking: Leading to deadlock risks

- Inheritance complicates thread safety: Subclasses might break parent class assumptions

The Mental Model Problem

Perhaps the biggest challenge is that shared mutable state requires developers to think about all possible interleavings of thread execution. This quickly becomes mentally overwhelming:

- With 2 threads and 3 operations each, there are 20 possible execution orders

- With 3 threads and 4 operations each, there are 369,600 possible execution orders

- With realistic applications having hundreds of threads... the complexity explodes

A Different Path Forward

The Actor Model addresses these problems by eliminating shared mutable state entirely. Instead of multiple threads accessing the same data:

- Each actor owns its state completely

- Communication happens only through messages

- No locks, no race conditions, no deadlocks

- Natural fault isolation and supervision

Consider how our ticket service might look with actors:

No synchronization keywords, no locks, no race conditions – just simple, sequential processing of messages.

Looking Ahead

The problems we've explored today – race conditions, deadlocks, livelocks, and starvation – have plagued concurrent programming for decades. Traditional OOP solutions, while functional, often create more complexity than they solve.

In our next article, we'll explore how the Actor Model provides elegant solutions to these challenges and dive into practical implementation patterns using Akka and Apache Pekko on the JVM.

The journey from shared mutable state to message-passing architectures isn't just about avoiding bugs – it's about building systems that are inherently more scalable, maintainable, and resilient to failure.

Next up in Part 3: We'll implement a complete Actor-based system, explore supervision strategies, and see how message-passing eliminates the concurrency pitfalls we've discussed today.